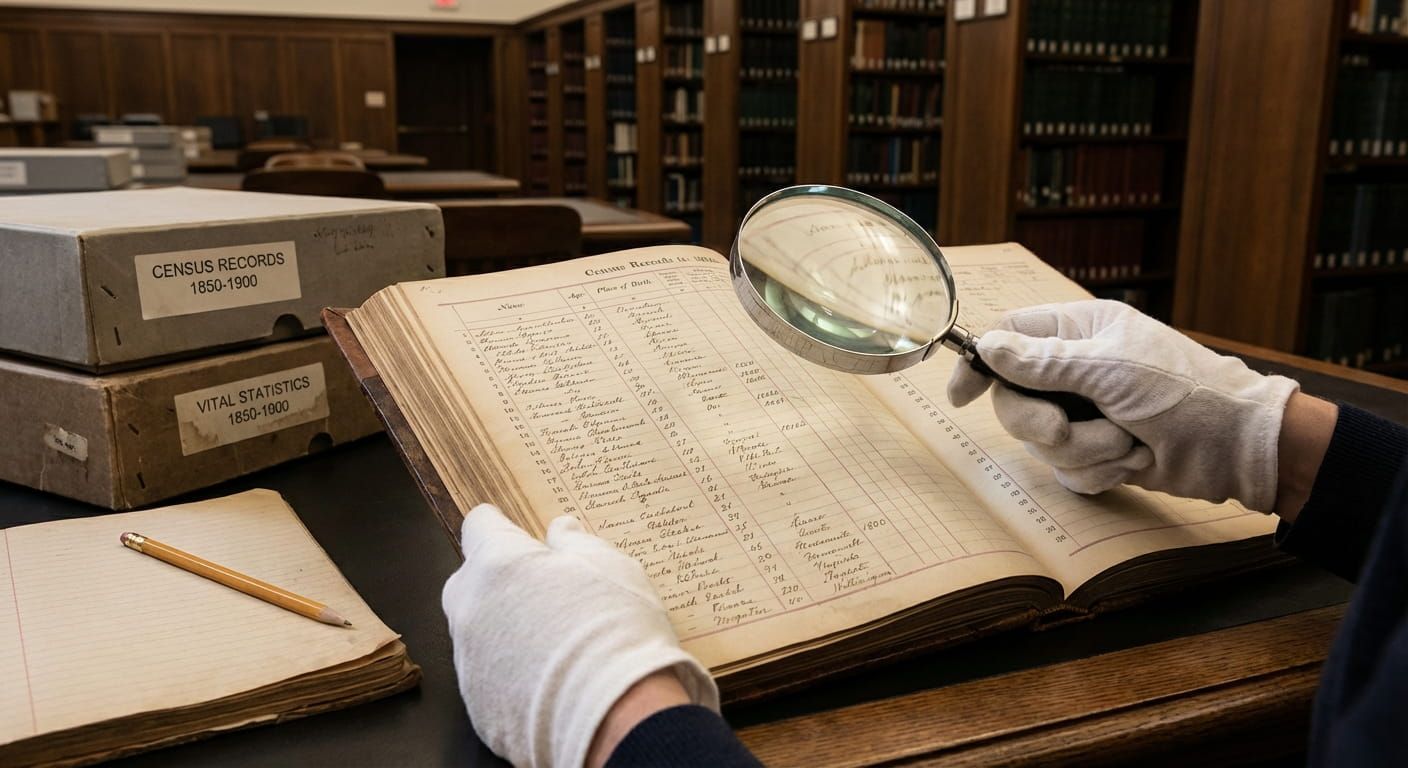

Old records rarely hand you a birth year on a clean silver platter. Instead, they leave clues, a stated age, a date of an event, a scribbled note in a margin, a secondhand memory from a neighbor. The good news is that these clues add up. With a steady method, you can turn messy ages in census pages, parish books, ship lists, and draft cards into a solid birth year range you can trust.

To find a birth year in historical records, treat every age as a clue with a margin of error. Anchor the age to a known event date, convert it into a birth year range, then compare that range across multiple documents. Watch for rounding, shifting census dates, calendar quirks, and different cultural age systems. A consistent pattern across sources earns confidence, while a single perfect number rarely does.

Practical Quiz for Birth Year Clues

Answer these to check your instincts before you start calculating. Your score appears instantly.

1) A census dated June 1 says someone is 29. What is the safest output for a birth year?

2) Two records disagree by two years. Which is the most common reason?

3) If a record uses a cultural age system where age counts from birth as one, what should you do?

Method for Turning Ages into Birth Year Ranges

Start with a simple rule, age without a full birth date is a range, not a point. If a record says someone is 40, that can mean they already had a birthday this year, or they have not yet had it. The range depends on the date the age was recorded.

If you do not know the record date, find it. Census schedules often have an official census day, even if the enumerator visited later. Draft registrations, marriage licenses, and baptism entries typically show the day the clerk wrote it down. Once you have that date, convert age into a birth year span and write it down as two endpoints. If you want help doing that cleanly, you can plug the dates into age calculator and record the output as a range rather than a single year.

Quote to keep beside your notes

A single record can be wrong, a pattern across records is harder to fake by accident.

Common Record Types and How Much Trust to Give Each One

Not all ages are created the same way. Some were provided by the person themselves. Others were guessed by an official. Some were copied from earlier paperwork. Knowing the usual pathway helps you choose a reasonable error margin.

Numbered Steps You Can Repeat for Every Person

- Write the record date. If the image shows only a year, look up the official day for that record set and add it to your notes.

- Record the age exactly as written. Include hints, for example “about 30” or “30 5 months.”

- Convert the age into a birth year range. Use the record date and subtract the age, then account for whether the birthday occurred yet.

- Label confidence. “High” for self reported exact birth date, “medium” for common census ages, “low” for neighbor supplied ages.

- Compare ranges across sources. Overlap is your friend. A tight overlap suggests you are close to the truth.

- Document the mismatch, not just the match. A disagreement can reveal a second marriage, name reuse, or a move between regions.

Age Differences That Reveal Family Structure

Sometimes your best clue is not the person’s age alone. It is the spacing between people listed in the same household. Parent ages, spouse ages, and sibling spacing can confirm whether you have the correct individual, especially with repeated names.

To test those relationships, calculate differences between two dates or two ages and see if the pattern makes sense. A tool built for this kind of comparison is age difference. Use it to check whether a stated parent child gap fits typical biology and local marriage patterns, without forcing it to match a modern norm.

- Parent child gaps can confirm whether a teenager is a child or a younger sibling.

- Sibling spacing can hint at missing children, miscarriages, or a second spouse with a younger set of kids.

- Spouse ages can support an identity match across towns where the surname is common.

- Older relatives living in the home can explain a surname change or a child raised by grandparents.

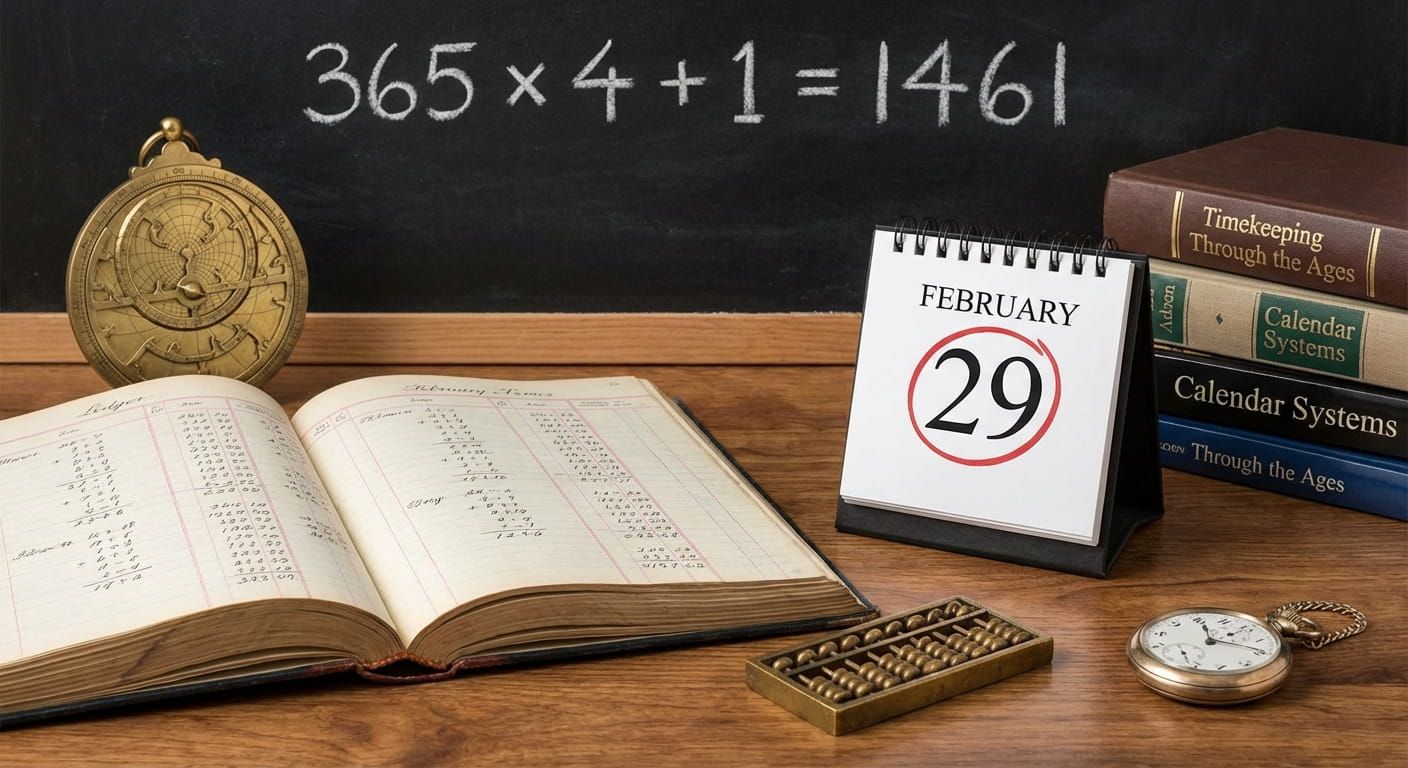

Calendar Details That Quietly Shift Birth Year Math

Even careful researchers get tripped up by the calendar. Leap days matter for exact age in days, and census dates are not always the same across decades. Some places changed how the new year was recorded. Some clerks wrote dates that look modern but were recorded under a different local rule.

If you want a clear explanation of why calendar rules can change an age outcome, read leap year math accurate calendar age counting. The key point is simple, use the correct record date, then accept a small uncertainty window unless the document gives a full birth date.

Census Ages, Rounding, and the Art of Acceptable Error

Census ages are famous for being slippery. Some enumerators rounded ages to the nearest five. Some families rounded on purpose because exact birthdays were not tracked closely. Some people did not know their birth year, especially if they were born in places without routine registration.

That does not mean census work is weak. It means you treat it as a framework. Look at multiple census years and watch the pattern. If someone is 20, 29, 38, and 50 across four censuses, the implied birth year should cluster, even if each single entry is off by a bit. When you see one age that breaks the pattern wildly, keep it, but assign it a lower confidence.

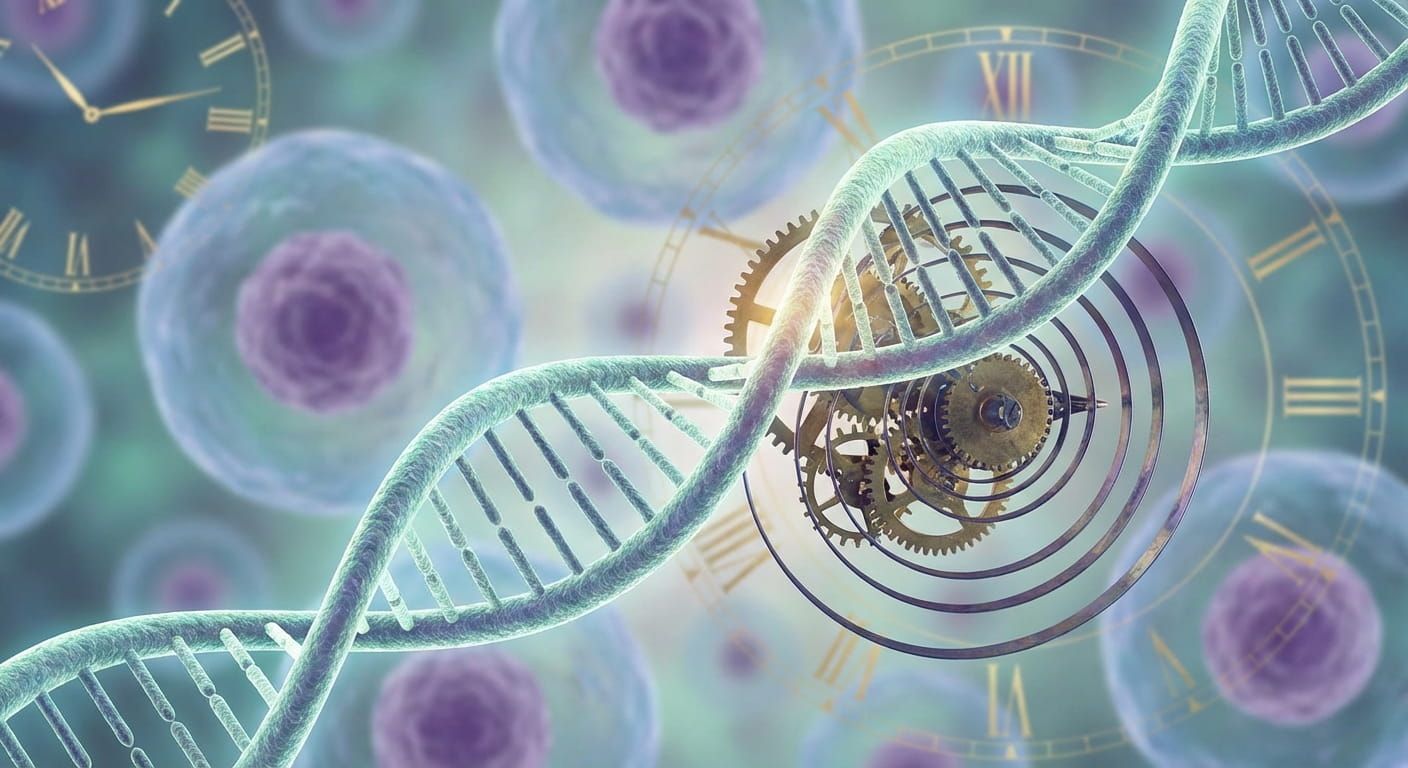

Handling Cultural Age Systems and International Records

Not every record uses the same idea of age. Some systems count age as one at birth. Some add a year at the new year, not on a birthday. Some records mix systems, especially in immigrant communities where the official form used one standard and the household used another.

A helpful background read is international age korean age. The practical takeaway for researchers is to test both interpretations. Subtract one year, or sometimes two, then check which version matches the rest of the evidence you have.

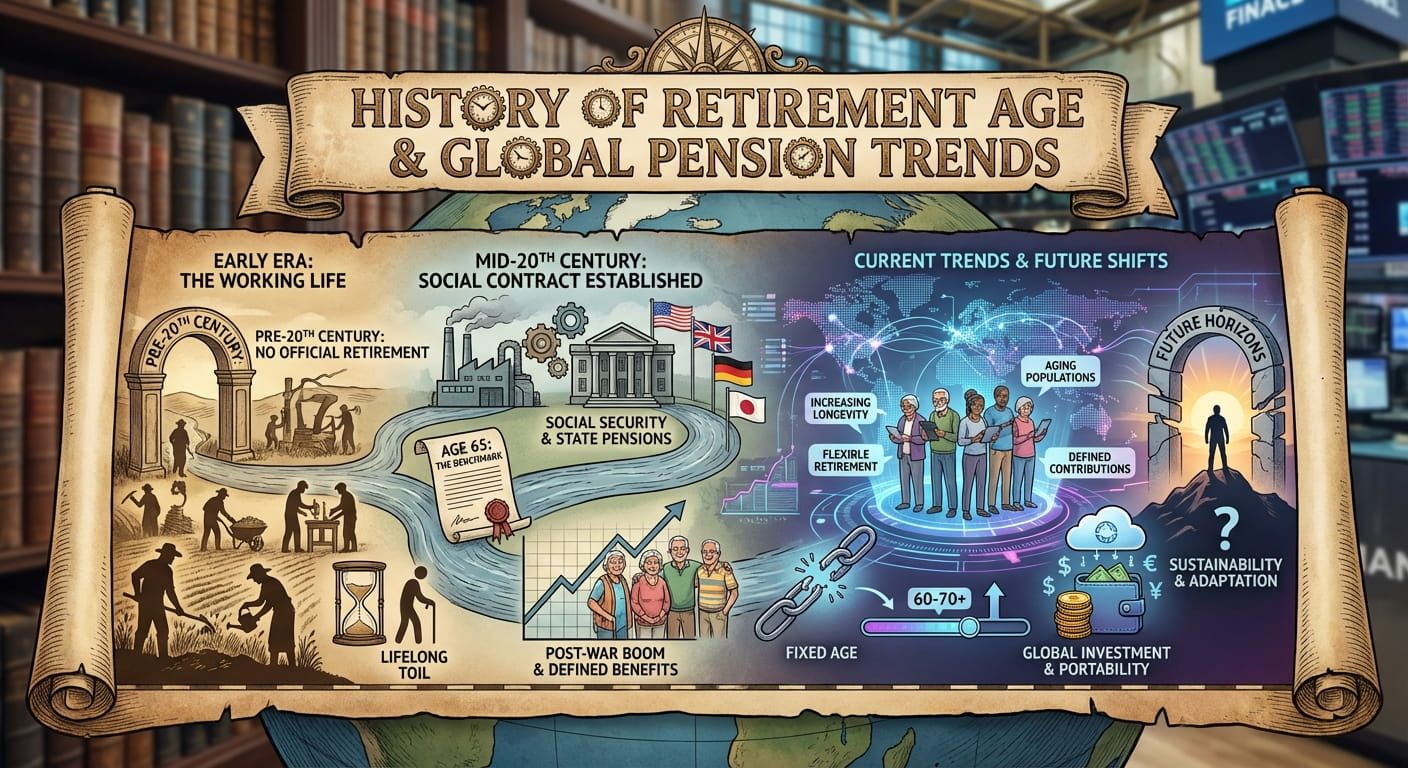

Generational Labels as a Sanity Check for Modern Records

For twentieth century and later research, generational labels can act as a quick sanity check. If an obituary implies a person belonged to a certain cohort, and your computed birth year lands far outside it, you may be mixing two individuals with the same name.

For a reference point, generations birth year labels can help you frame the era you are working in. Treat it as a rough guardrail, not a proof.

Using Event Based Age Notes to Back Calculate a Birth Year

Many documents do not list a birth year at all, but they give ages at major events. Think of a ship manifest that lists age at arrival, a newspaper article that calls someone “aged 73,” or a pension file that states “aged 62 at enlistment.” Your job is to anchor that age to an event date, then back calculate.

If you want a simple way to test several event dates without redoing math each time, how old was I can help you convert between an event date and an estimated birth date range. Use it to speed up your workflow, then write down the range and the source citation in your notes.

Historical Context That Explains Why Ages Drift

Age reporting sits inside a culture. In some eras, birthdays were private family knowledge, not a public record. In other times, age affected taxes, military service, marriage consent, and voting. Those pressures can nudge reported ages up or down.

For a look at how birthday customs changed across time and place, cultural birthday history offers useful context. This matters because it explains why a grandmother might know her children’s birthdays but not her own, or why a clerk might estimate an age without anyone objecting.

Mini Toolkit for Research Sessions

These practical habits keep you steady when the archive gets noisy, and they fit into one paragraph for easy scanning:

Keep a running timeline, cite every source image, write ages exactly as written, convert ages into ranges, record where the range came from, compare overlaps, note conflicts plainly, and avoid locking in a single year until at least two independent sources support it.

If you want a focused tool made for this style of work, historical age can support timeline based reasoning, especially when you are juggling many dated events and age notes for the same person.

Red Flags That Signal You Might Have Two People

Birth year confusion is often an identity confusion. Common names, reused family names, and stepfamilies can create nearly identical profiles. Look for red flags that suggest you may be combining two lives into one.

- Two different spouse names with overlapping dates

- Children born before the parent would be biologically plausible

- A sudden change in birthplace or occupation without a migration trail

- A census household that repeats the same first names in a different order

- A gap of many years where no records show up, then a reappearance with a shifted age pattern

Case Example That Shows the Range Approach Working

Suppose a census official day is June 1, 1900 and the record lists Maria as 29. That implies she was born between June 2, 1870 and June 1, 1871, depending on whether her birthday happened before the census day. Next you find a marriage record dated October 15, 1894 listing her as 23. That implies a birth between October 16, 1870 and October 15, 1871. Those ranges overlap strongly, pointing to late 1870 through mid 1871 as a likely window.

Now add a third piece. A death record says she died March 3, 1932 aged 61. That implies a birth between March 4, 1870 and March 3, 1871. This still overlaps, and it nudges the likely window toward 1870. You have not pinned a single year with certainty, but you now have a tight range supported by three independent events. That is strong genealogy work.

Where the Paper Trail Meets Your Best Judgment

Finding a birth year in historical records is less about hunting for one magical line and more about building a small case. Dates, ages, and relationships all testify. Some witnesses are shaky. Some are strong. Your job is to weigh them, keep your notes honest, and let the overlapping evidence speak. The reward is not only a more accurate birth year, but a clearer picture of how a person moved through time, one record at a time.