New Year’s Eve is a universal celebration, yet the very moment it begins is not the same everywhere. When fireworks burst over Sydney, the sun still shines in Los Angeles. This uneven rhythm of time is stitched together by invisible lines on our planet’s surface, and none is stranger than the International Date Line. It refuses to behave, twisting like a ribbon across the Pacific. Let’s unravel why it zigzags instead of cutting cleanly through the globe.

The Idea Behind the Line That Divides Days

Time zones slice the Earth into twenty-four vertical strips. Each roughly represents an hour of difference from its neighbors. The International Date Line, sitting mostly at the 180° meridian, marks the place where one day turns into the next. When you cross it from west to east, you go back a day. Step from east to west, and you leap ahead.

That sounds simple on paper. But the planet isn’t governed by geometry alone. Politics, trade, and everyday life shape where these lines actually fall. The Date Line is the biggest example of compromise between mathematical logic and human life.

A Short Journey Through Timekeeping

Before the late 19th century, time was a local affair. Each town set its clocks by the sun overhead. Noon was when the sun was highest. That worked fine until trains and telegraphs connected places faster than the sun moved across the sky. Suddenly, people needed consistent time references. Thus came time zone standards, agreed upon in 1884 during the International Meridian Conference in Washington D.C.

The Greenwich Meridian in England was chosen as zero longitude. Opposite it, halfway around the world, the 180° line became the natural place for the date to change. Yet, as people soon discovered, “natural” doesn’t always mean practical.

The Flexibility of Human Geography

Imagine you live on an island just west of the 180° line. Your nearest trading partner lies to the east. If the Date Line runs straight, your calendars would differ by a full day. A Monday for you would be a Tuesday for your neighbor. Schools, businesses, and flights would all be confusing.

To prevent that, the line bends around groups of islands and territories. This keeps neighboring communities in sync with their economic and cultural ties rather than with strict longitude.

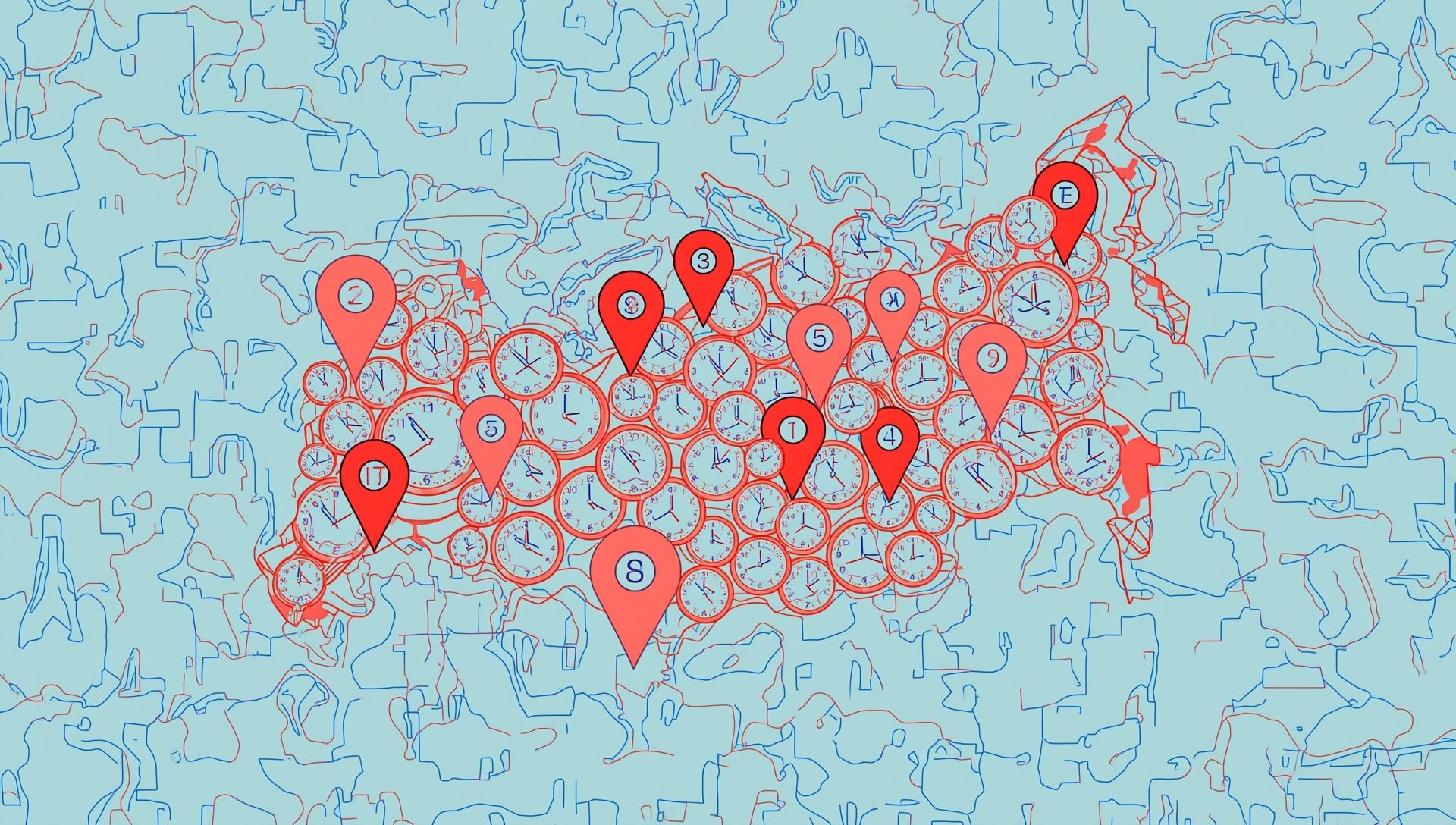

Here’s a quick overview of major regions affected by the Date Line’s quirks:

- Kiribati adjusted its time in 1995 to align all its islands on the same day.

- American Samoa and Samoa, though geographically close, are separated by the line due to trade preferences.

- The Aleutian Islands of Alaska curve west but remain on the same calendar as the United States.

| Region | Local Choice | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Kiribati | Shifted Date Line eastward | Unified all islands under same day |

| Samoa | Moved west of the line in 2011 | Synced with New Zealand & Australia |

| Alaska | Stayed east of the line | Remained in U.S. time framework |

How Politics Bent the Line

When the International Date Line was proposed, it didn’t come with rigid enforcement. Each country was free to adjust the line’s course for its own reasons. The result was a jagged path reflecting global diplomacy rather than scientific neatness.

Take Samoa, for example. In December 2011, it decided to jump the line overnight. Literally. The country skipped December 30 entirely to align its weekdays with Australia and New Zealand, its biggest trade partners. The switch meant Samoans celebrated New Year’s first instead of last. One small island nation rewrote its place in time.

The Science of a Non-Scientific Line

Technically, nothing in physics requires the Date Line to exist. The Earth rotates, and time zones are human inventions to manage that motion. The Date Line simply ensures that when clocks keep moving forward, calendars don’t drift endlessly out of sync. Without it, our sense of “today” would vanish every time we circled the globe.

Still, the actual position of the line depends entirely on people, not the planet. For navigators, it serves as a practical boundary. For governments, it’s a tool to align commerce. For travelers, it’s a reminder that time is as social as it is scientific.

Why It Looks Crooked on the Map

Flat maps distort reality. On a globe, the Date Line makes soft curves. On a two-dimensional map, those bends stretch and twist dramatically. The Pacific Ocean’s wide expanse makes it easy to let the line swerve without slicing through populated areas. Cartographers exaggerate these turns to keep the geography readable, as you can see in any time zone map.

The result looks chaotic, but the bends are deliberate. They weave around landmasses, keeping countries like Fiji, Tonga, and Kiribati intact within one calendar. This avoids splitting national territories into two separate days.

The New Year’s Connection

Every December 31st, the Date Line turns into the starting gate of global celebration. The first cheers echo from islands like Kiritimati in Kiribati, while the last ones come from places like Baker Island, a U.S. territory nearly a full day behind.

This sequence, where New Year’s rolls westward hour by hour, owes its drama to the line’s crookedness. Without its shape, we wouldn’t enjoy the slow parade of fireworks circling the planet. From Tonga’s beaches to Times Square’s confetti, every celebration is part of a wave passing over that zigzagging line.

Here’s a fun look at the order of celebration:

The Practical Side of Keeping It Crooked

A straight Date Line would create headaches for airlines, shipping routes, and even data centers. Imagine an airplane flying over islands that technically switch dates mid-flight. A curved line prevents confusion, keeping air and sea navigation simpler.

The irregular shape also helps digital systems that rely on synchronized timestamps. Global companies, from satellite networks to finance hubs, benefit when local regions share the same day. That’s why governments maintain the bends, even in the age of internet precision.

- The Date Line runs mostly through open ocean to avoid human settlement conflicts.

- There is no official international organization that enforces its shape.

- Changes to the line occur through national declarations, not global votes.

When the Calendar Itself Takes Sides

Sometimes, calendar alignment reveals deep cultural identity. Tonga and Samoa share Polynesian roots but stand on opposite sides of the line. For one, the weekend begins while for the other it’s still the day before. The choice isn’t just about business; it reflects how people see themselves connected to the wider world.

A single stroke on a map can define when communities rest, work, and celebrate. That’s the strange beauty of the Date Line. It makes time feel human again.

How the Line Connects Us All

Every New Year, television networks broadcast the rolling wave of midnight fireworks across the globe. We watch as the world turns, city by city, hour by hour. Behind that spectacle lies the International Date Line quietly organizing the rhythm of celebration. Its twists, its political turns, and its refusal to be straight all remind us that time isn’t just measured by clocks but by connection.

The line’s bends tell a story of cooperation and cultural respect. It’s proof that even the world clock bends toward human needs. Whether you’re ringing in the new year on a beach in Fiji or sipping coffee in New York, you’re part of a planet held together not by perfect symmetry but by shared moments that cross oceans and calendars alike.