The calendar we use today seems simple: twelve months, 365 days, and a leap year every four years. Yet this structure took thousands of years to form. It’s the product of countless civilizations observing the skies, marking the seasons, and trying to bring order to time. Our modern Gregorian calendar didn’t appear overnight. It grew from trial, error, and remarkable astronomical insight. The story of how humanity learned to measure time is also the story of how we learned to live together through shared rhythms.

- Modern calendars evolved from ancient lunar and solar systems used by Egyptians, Babylonians, Greeks, and Romans.

- The Julian calendar introduced the concept of leap years, improving accuracy over earlier systems.

- The Gregorian calendar refined this further to align better with Earth's orbit around the Sun.

- Today’s calendar remains a mix of scientific precision and cultural tradition rooted in ancient timekeeping.

The Birth of Time Measurement

Long before written history, early humans tracked time by watching natural cycles. The Moon’s phases, the rising of stars, and the changing of seasons served as the first calendars. Hunters and farmers needed to know when to migrate, plant, or harvest. Communities marked these transitions with rituals that tied time to survival and spirituality, much like how we now mark holidays and seasonal observances.

The word “calendar” comes from the Latin calendae, meaning “the first day of the month.” In ancient Rome, it referred to the days when debts were due, linking timekeeping directly to economics and civic life. Even in its earliest form, the calendar was more than a record of days; it was a social contract.

Lunar Calendars and the Moon’s Influence

One of the earliest forms of organized timekeeping was the lunar calendar. The Moon’s 29.5-day cycle made it a natural way to count months. Ancient Babylonians, Egyptians, and Chinese all began with lunar systems. A year of twelve lunar months totaled about 354 days, leaving an annual gap of roughly eleven days compared to the solar year.

To correct this, early societies developed ways to “intercalate,” or add, extra days or months to keep calendars aligned with the seasons. This balancing act was vital. Without it, months that once marked harvest would eventually drift into winter, similar to the drift corrected by leap years in our modern system.

The Babylonian calendar, used around 1900 BCE, introduced the practice of adding an extra month every few years, one of the first attempts to reconcile lunar and solar cycles.

The Egyptian Solar Calendar

The ancient Egyptians were among the first to adopt a solar calendar. They noticed that the annual flooding of the Nile corresponded with the heliacal rising of the star Sirius. This observation allowed them to fix the year at 365 days, divided into twelve 30-day months, plus five additional festival days at the end of the year.

This solar calendar was remarkably accurate for its time, but it lacked a leap year system. As a result, the New Year drifted slowly through the seasons over centuries. Despite this drift, Egypt’s calendar profoundly influenced Greek and Roman timekeeping later on, laying groundwork for the modern evolution of calendars.

The Greek and Babylonian Legacy

The Greeks inherited Babylonian methods but added sophistication. They used a lunisolar system, coordinating both Moon cycles and solar motion. The astronomer Meton of Athens introduced a 19-year cycle that synchronized 235 lunar months with 19 solar years. Known as the Metonic cycle, it became a foundation for later calendars, including the Hebrew and Christian systems.

This innovation demonstrated how mathematical astronomy began to shape timekeeping. People were no longer content with rough estimates; they wanted celestial precision, a pursuit still reflected in today’s time zones and atomic standards.

The Roman Calendar: From Chaos to Reform

The Roman calendar started as a lunar system with ten months, leaving a gap in winter when no months were named. Later, January and February were added to fill the year. Political manipulation often threw it into disorder, as leaders extended or shortened years for convenience.

By 46 BCE, the system was so unreliable that Julius Caesar ordered a complete reform. With help from Egyptian astronomers, he introduced the Julian calendar. This new model established a 365-day year with an extra day added every four years, the leap year. It was a major step forward in aligning civic and solar time, the kind of precision modern digital timekeeping tools now provide effortlessly.

Julius Caesar’s calendar reform added 90 extra days to 46 BCE to realign months with the seasons. That year became known as “the year of confusion.”

The Julian Calendar’s Strengths and Flaws

The Julian system worked well but slightly overestimated the length of a year. The actual solar year is about 365.2422 days, not 365.25. That tiny difference, just eleven minutes per year, gradually added up. By the 1500s, the calendar was off by about ten days, causing the spring equinox to fall earlier than expected. This error affected the calculation of Easter and other important religious observances.

To fix it, a more accurate calendar was needed. That’s where Pope Gregory XIII entered the picture, refining the system to become what we now call the Gregorian calendar.

The Gregorian Calendar and Its Global Spread

In 1582, the Gregorian calendar replaced the Julian version in much of Europe. It refined leap year rules: century years would not be leap years unless divisible by 400. This correction realigned the equinox and improved long-term accuracy.

For example, 1600 and 2000 were leap years, but 1700, 1800, and 1900 were not. This adjustment keeps the Gregorian calendar within one day of the solar year for more than 3,000 years.

Adoption, however, was slow. Catholic countries changed first, while Protestant and Orthodox nations followed gradually. Britain and its colonies switched in 1752, skipping eleven days to catch up. Russia waited until after the 1917 revolution. Today, almost every country uses the Gregorian calendar for civil purposes, though many maintain different calendar systems alongside it.

| Calendar | Type | Introduced By | Correction Applied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian | Solar | Ancient Egypt | None (no leap years) |

| Babylonian | Lunar | Ancient Mesopotamia | Intercalation of months |

| Julian | Solar | Julius Caesar, 46 BCE | Leap year every 4 years |

| Gregorian | Solar | Pope Gregory XIII, 1582 CE | Skip leap years except when divisible by 400 |

Other Timekeeping Traditions

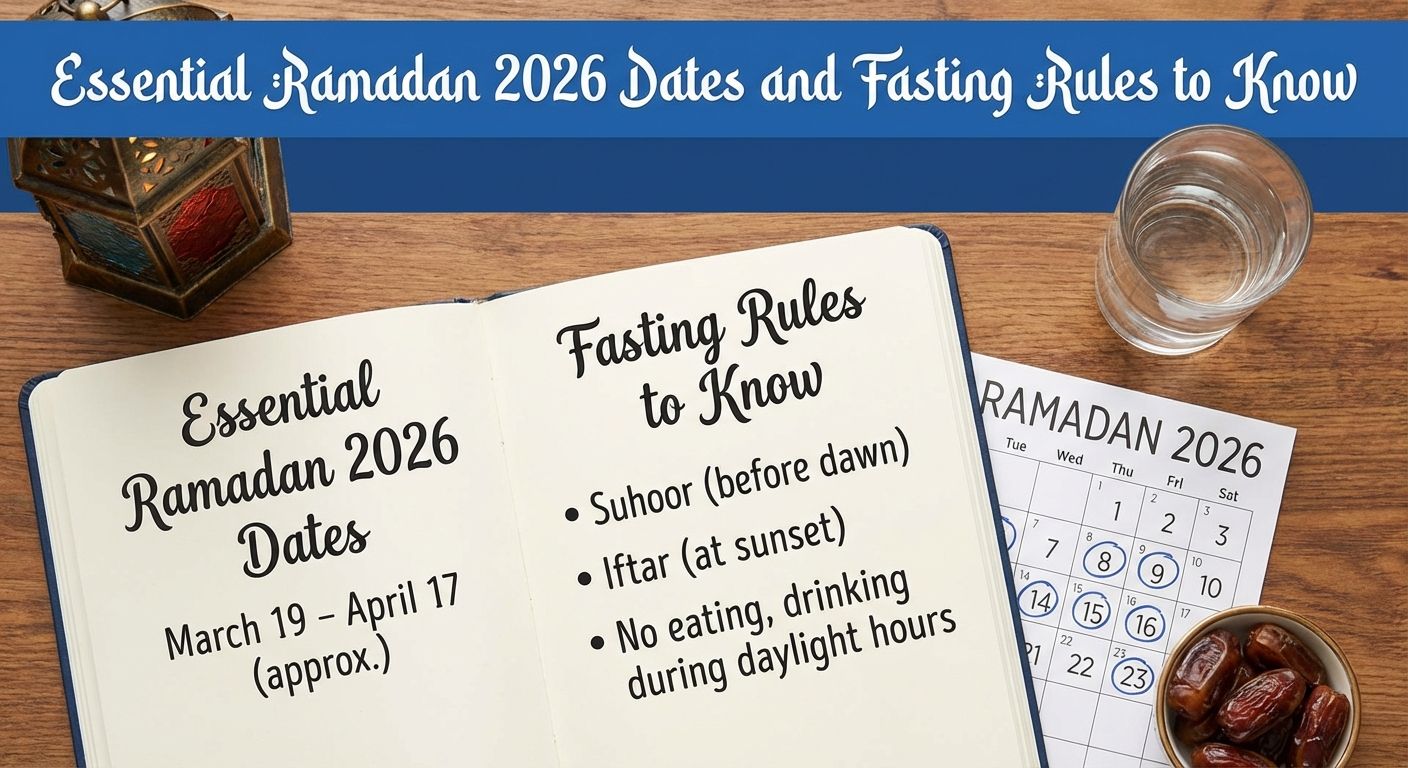

While the Gregorian system dominates global use, other calendars continue to thrive. The Islamic calendar is lunar, beginning with the Hijra of Prophet Muhammad in 622 CE. The Hebrew calendar is lunisolar, adjusting with leap months. The Chinese calendar also blends lunar and solar cycles, anchoring festivals like the Lunar New Year. These systems reflect cultural values that link time to faith and seasonal life.

- The Gregorian calendar was designed to correct a drift of about ten minutes per year from the Julian system.

- Leap year rules keep our seasons aligned with Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

- Despite its accuracy, some cultures still use lunar or regional calendars alongside the Gregorian one.

- Modern digital calendars, such as time.now/calendar, can display multiple systems simultaneously.

From Stars to Software: Timekeeping in the Modern Era

Our ancestors relied on shadows, stars, and seasons to track time. Today, we rely on atomic clocks and satellite signals. Yet the principle remains the same: to align human life with natural patterns. Modern tools allow us to plan efficiently with options like event planners and world clock synchronization, bridging ancient rhythm with digital precision.

Still, the heart of timekeeping hasn’t changed. It’s about connection. Whether ancient farmers watched the Moon rise or modern users coordinate across global time zones, we all share a need to understand where we stand in the rhythm of time.

The Legacy of Ancient Wisdom

The modern calendar may appear simple, but it carries the wisdom of thousands of years. Every adjustment, from Egyptian solar observations to Gregorian reform, represents humanity’s effort to understand the universe and live in harmony with it. Our timekeeping system is a bridge between ancient starlight and digital precision, a living record of curiosity, culture, and progress.

In the end, the calendar is more than dates and numbers. It is a mirror of how civilization measures meaning. From the first shadow cast on a stone to the synchronized pings of global time servers, the journey of the calendar reflects our deepest wish to make sense of time, a quest that continues to shape everything from world clocks to modern scheduling systems.