Every spring and autumn, clocks around the world shift by one hour, sparking a mix of confusion, debate, and routine adjustments. This practice, known as Daylight Saving Time (DST), affects billions of people every year. Yet few stop to ask where it came from or why it exists in the first place. The story of DST is filled with interesting twists, clever ideas, and centuries of evolving attitudes about time, light, and productivity.

Before Daylight Saving Time Existed

Before the invention of modern timekeeping, people lived by the natural rhythm of the sun. Farmers and tradesmen started work at sunrise and ended at sunset, adjusting their days with the seasons. Clocks were set locally, not nationally, which meant noon in one town could differ from noon in another.

The idea of standardized time emerged in the 19th century with the rise of railways and industrialization. Train schedules demanded consistency, leading to the creation of formal time zones. Yet even as time became standardized, the problem of how to make the most of daylight persisted.

The Earliest Proposals for Saving Daylight

The first known proposal to adjust daily schedules for daylight came from Benjamin Franklin in 1784. While living in Paris, Franklin humorously suggested that people could save money on candles if they woke up earlier and used natural light instead. His essay was satirical, but the seed of an idea was planted: shift human routines to align with daylight and reduce waste.

Franklin’s idea did not immediately lead to formal clock changes. However, the industrial era brought renewed interest in efficiency. As cities expanded and artificial lighting became widespread, thinkers began to see the potential benefits of organizing society’s hours more strategically, a topic explored further in the origins of DST.

The Modern Invention of DST

The credit for modern Daylight Saving Time goes to George Vernon Hudson, a New Zealand entomologist. In 1895, Hudson proposed a two-hour time shift to give himself more daylight after work for collecting insects. His idea was taken seriously by scientific societies and eventually discussed in government circles.

A few years later, British builder William Willett championed the concept publicly. He proposed moving clocks forward by 20 minutes each Sunday in April and back again in September to make better use of natural light. Willett’s campaign gained attention but faced strong resistance from politicians and farmers. Sadly, he died in 1915, just a year before his idea became reality, paving the way for the first official clock changes.

The First Countries to Implement DST

Daylight Saving Time officially began during World War I. Germany and Austria-Hungary adopted it in 1916 as a wartime measure to conserve coal and energy. Britain followed soon after, and by 1918 the United States had joined in.

During the war, energy consumption soared. DST was seen as a simple way to reduce electricity use and improve productivity. The practice spread quickly through Europe and North America, becoming part of civilian life even after the war ended.

The Interwar and World War II Years

After World War I, some countries abandoned DST, only to reinstate it during World War II. The United States and Britain, among others, reintroduced it as part of broader efforts to save resources and maintain production efficiency. In the U.S., President Franklin D. Roosevelt called it “War Time” and kept clocks permanently one hour ahead for the duration of the war.

By this point, DST had moved from a simple idea to a global experiment in time management. However, once the war ended, confusion set in. Different regions set their own schedules, leading to time discrepancies across borders and inconsistencies that modern world clocks help prevent today.

Standardization and the Postwar Era

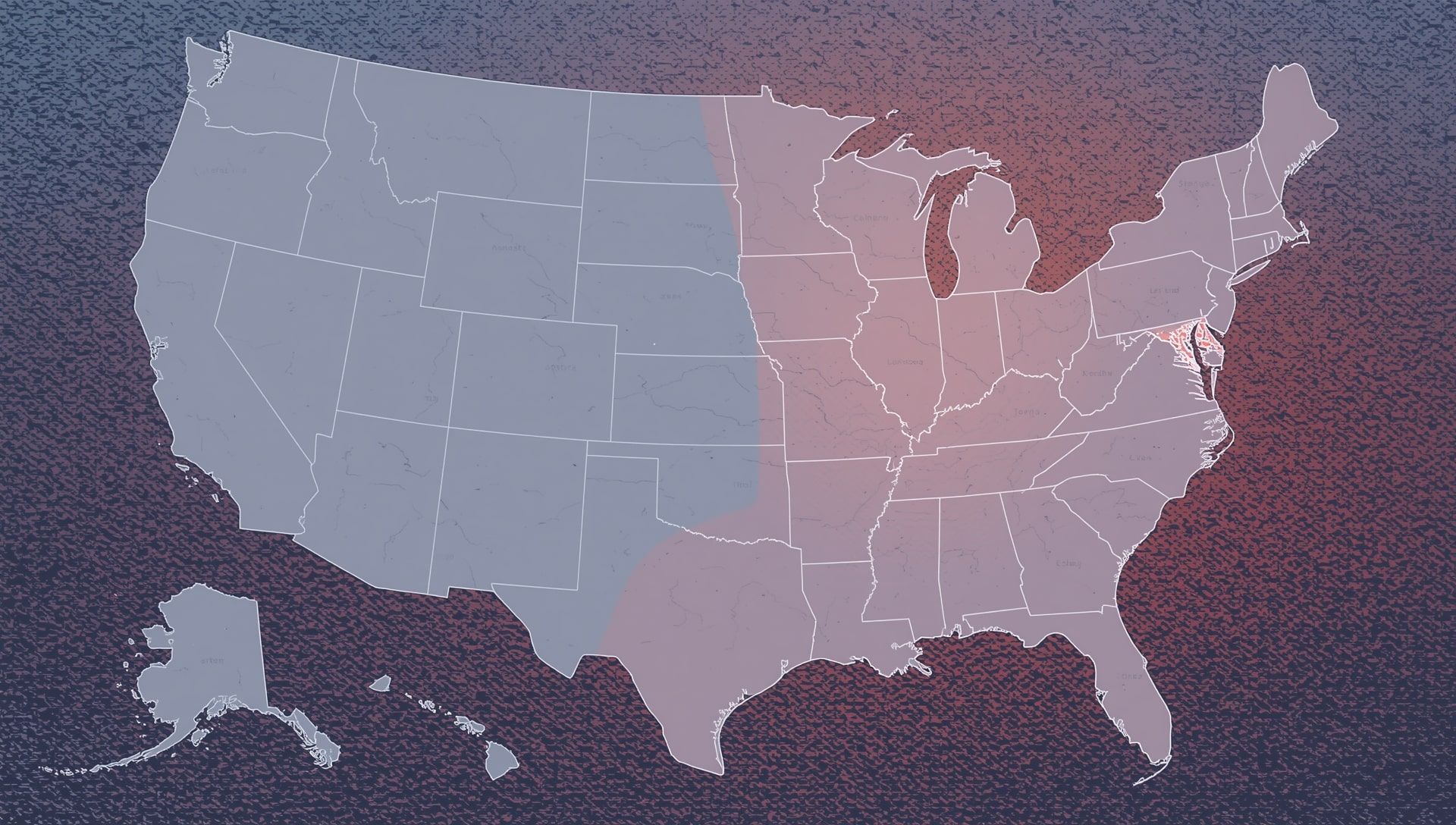

In 1966, the United States passed the Uniform Time Act to standardize the start and end dates of Daylight Saving Time across the nation. Before that, local governments could decide whether or not to observe DST, which caused chaos for travelers and broadcasters.

The act established that clocks would spring forward in late April and fall back in late October, creating a unified national system. Over time, adjustments have been made, and since 2007, the U.S. observes DST from the second Sunday in March to the first Sunday in November. These standardized rules are based on internationally recognized IANA time zone identifiers.

How DST Spread Around the World

Although many countries adopted DST during the 20th century, not all have kept it. Some found it unsuitable for their geography or climate. Near the equator, daylight length changes little between seasons, making DST unnecessary. In contrast, countries farther from the equator benefit more from extended daylight hours.

- Europe adopted DST widely after the 1970s energy crisis, hoping to reduce electricity use.

- Many Asian countries tried it briefly but discontinued it after minimal energy savings.

- Australia and New Zealand use DST in some regions but not others, due to differences in daylight hours.

- African nations generally do not observe DST because daylight variation is small year-round.

Modern Adjustments and Controversies

Today, DST is both widespread and contested. Supporters claim that it promotes outdoor activity, reduces evening energy use, and boosts commerce. Opponents argue that its benefits are outdated and that the time changes disrupt sleep, health, and productivity.

Studies have shown that while DST once saved measurable energy, modern electricity use patterns dominated by air conditioning, heating, and electronics have largely erased those gains. The health effects of sleep disruption and the risk of accidents after clock changes have also fueled calls to abolish it. These debates mirror those seen in discussions about standard time versus DST.

Key Historical Milestones

- 1784: Benjamin Franklin publishes his essay on saving daylight.

- 1895: George Vernon Hudson proposes the first modern DST concept in New Zealand.

- 1907: William Willett campaigns for British Summer Time in the UK.

- 1916: Germany implements the world’s first official DST policy during World War I.

- 1918: The United States adopts DST nationally for the first time.

- 1942: President Franklin D. Roosevelt institutes “War Time” during World War II.

- 1966: The U.S. passes the Uniform Time Act, standardizing DST schedules.

- 2007: The U.S. extends DST by several weeks to match energy policy goals.

Global Trends Today

As of today, roughly 70 countries still observe Daylight Saving Time, mostly in Europe, North America, and parts of the Middle East. Many nations in Asia, Africa, and South America have discontinued the practice entirely.

The European Union has even proposed ending the biannual clock change, allowing each member country to choose permanent summer or winter time. Meanwhile, in the United States, the Sunshine Protection Act aims to make DST permanent, though it has yet to pass both houses of Congress.

Why DST Still Matters

Even as the world debates its usefulness, DST continues to influence how societies think about time and daylight. It reminds us that time is not just a mechanical measure but also a social agreement, shaped by human priorities and history. Whether it stays or goes, DST remains one of the most fascinating examples of how people have tried to control time itself, affecting everything from events scheduling to international communication.

From Past to Present

Daylight Saving Time began as an idea to make better use of sunlight and conserve energy. Over the decades, it evolved into a global system of time management, one that reflects changing lifestyles and technologies. What started as a wartime necessity and an inventor’s dream now sits at the crossroads of tradition and reform.

The debate over DST continues, but its story shows how human innovation and practicality often meet in surprising ways. Whether you love it or hate it, the history of Daylight Saving Time proves one thing: our relationship with time is never set in stone.