When Daylight Saving Time (DST) was first introduced, the goal was clear: reduce energy use by taking advantage of longer daylight hours. The logic was simple, if people had more light in the evening, they would use less electricity. Over a century later, that assumption is being questioned. With modern lifestyles, technology, and changing energy consumption patterns, does DST really save energy anymore, or has it become an outdated habit?

The Origins of Energy Saving Through DST

The concept of adjusting clocks for energy efficiency dates back to the early 20th century. During World War I, several countries adopted DST as a wartime measure to conserve fuel. The idea was that people would make better use of daylight and reduce reliance on artificial lighting in homes and workplaces. This early adoption is explored in detail in the origins of DST.

When the war ended, many nations dropped the practice. Yet during World War II, DST returned as part of a broader effort to conserve energy and resources. For decades, the rationale remained tied to lighting and electricity use. But as technology advanced, the original argument began to lose strength.

How DST Was Supposed to Save Energy

The principle behind DST is straightforward. By moving clocks forward in spring, people get more daylight in the evening. This should mean less time using lights and possibly shorter periods of energy consumption in the evening. In theory, it balances human activity with natural light, a concept similar to the logic behind standard versus daylight time.

- More daylight in the evening reduces household lighting needs.

- Shifting waking hours closer to sunrise maximizes natural light use.

- Evening activities move outdoors, lowering indoor electricity demand.

In an era when incandescent bulbs were the dominant source of light and energy costs were high, this strategy made sense. But the modern energy landscape is far more complex.

The Modern Reality of Energy Use

Today, the way we consume energy is completely different. Lighting is no longer the largest component of residential electricity use. Instead, heating, cooling, and electronic devices dominate the load. This shift changes how DST affects total consumption, as shown in modern DST energy studies.

Modern studies reveal that while DST can slightly reduce lighting demand, it often increases energy use for air conditioning and heating. For instance, people use more cooling during warm, bright evenings and more heating during colder, darker mornings.

What the Data Shows Around the World

Different regions experience different effects depending on climate, geography, and lifestyle. Here is what research has shown from around the world:

| Region | Findings | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| United States | Energy savings are minimal; higher use of air conditioning offsets lighting reductions. | 0.1–0.5% average reduction |

| Europe | Mixed results, with savings primarily in lighting but increased heating needs in northern countries. | Neutral to slightly positive |

| Australia | Southern regions saved small amounts of energy; northern regions saw no benefit. | Highly dependent on climate |

| Japan | Studies show negligible or zero savings due to advanced efficiency and mild daylight variation. | No measurable change |

While results vary, the pattern is clear: the more energy a society spends on heating and cooling, the less effective DST is as a conservation strategy.

Why DST’s Effectiveness Has Declined

Several modern developments have reduced DST’s usefulness as an energy-saving tool:

- Efficient Lighting: LED bulbs use up to 80 percent less energy than traditional incandescent lights, making the original savings nearly irrelevant.

- Climate Control: Heating and air conditioning now represent the largest portion of household energy use. DST tends to increase both at different times of year.

- Digital Devices: Computers, TVs, and other electronics consume power constantly, regardless of daylight.

- Flexible Work Schedules: With remote work and flexible hours, fewer people follow the same daily routine tied to sunrise and sunset.

- Urbanization: City lights and artificial illumination dominate, reducing the role of natural daylight in energy consumption.

In short, the modern world no longer runs on the assumptions that made DST logical a century ago.

When DST Might Still Help

Not every study shows DST to be useless. Under certain conditions, it can still offer small advantages. In regions with mild weather and limited air conditioning use, DST may slightly reduce evening energy demand. The savings might be small in percentage terms but significant for utilities managing large power grids.

- Households in cooler climates save modestly during spring and autumn.

- Countries closer to the equator see little or no benefit because daylight varies little year-round.

- Some southern European and North American states report noticeable lighting reductions during peak months.

While these effects are real, they are rarely large enough to justify the disruption caused by changing clocks.

The Hidden Costs of DST

DST may not save much energy, but it does introduce other costs. Studies have linked the twice-yearly clock change to a range of temporary disruptions. These include:

- Increased risk of heart attacks and workplace accidents after the spring shift, as discussed in health studies on DST.

- Lower productivity during the first few days of adjustment.

- Confusion in travel, logistics, and digital scheduling systems.

- General dissatisfaction among the public due to disrupted sleep cycles.

Energy Savings: Then vs. Now

To understand how dramatically DST’s role has changed, it helps to compare the context of a century ago with today’s reality.

| Time Period | Main Energy Use | Impact of DST | Relevance Today |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early 1900s | Lighting (oil lamps, early electricity) | Significant savings in lighting fuel | High |

| Mid-20th Century | Lighting and heating | Moderate savings, still beneficial | Medium |

| 21st Century | Heating, cooling, digital devices | Negligible or negative savings | Low |

The transformation of energy consumption patterns means that the simple “longer days equal less power” equation no longer holds true.

Environmental Considerations

At a time when the world focuses on cutting carbon emissions, DST’s minimal energy savings appear even less relevant. Any potential reduction in electricity use is often offset by increased fossil fuel consumption for heating and transportation.

Some experts argue that other strategies, such as improving building insulation, promoting efficient appliances, or investing in renewable energy, are far more effective at reducing environmental impact than seasonal time shifts.

Why Governments Still Use DST

Despite its limited energy benefits, DST persists in many countries. Part of the reason is cultural inertia: people are accustomed to the rhythm of lighter evenings in summer. Another factor is coordination. Changing or abolishing DST requires international agreement, especially in regions like Europe or North America where cross-border synchronization is vital. This is why discussions often arise alongside EU DST reform efforts.

There are also psychological and social reasons. Longer evenings encourage outdoor activities, which can boost morale and public engagement. For this reason, governments often frame DST as a lifestyle benefit rather than an energy-saving measure.

Public Opinion and Ongoing Debates

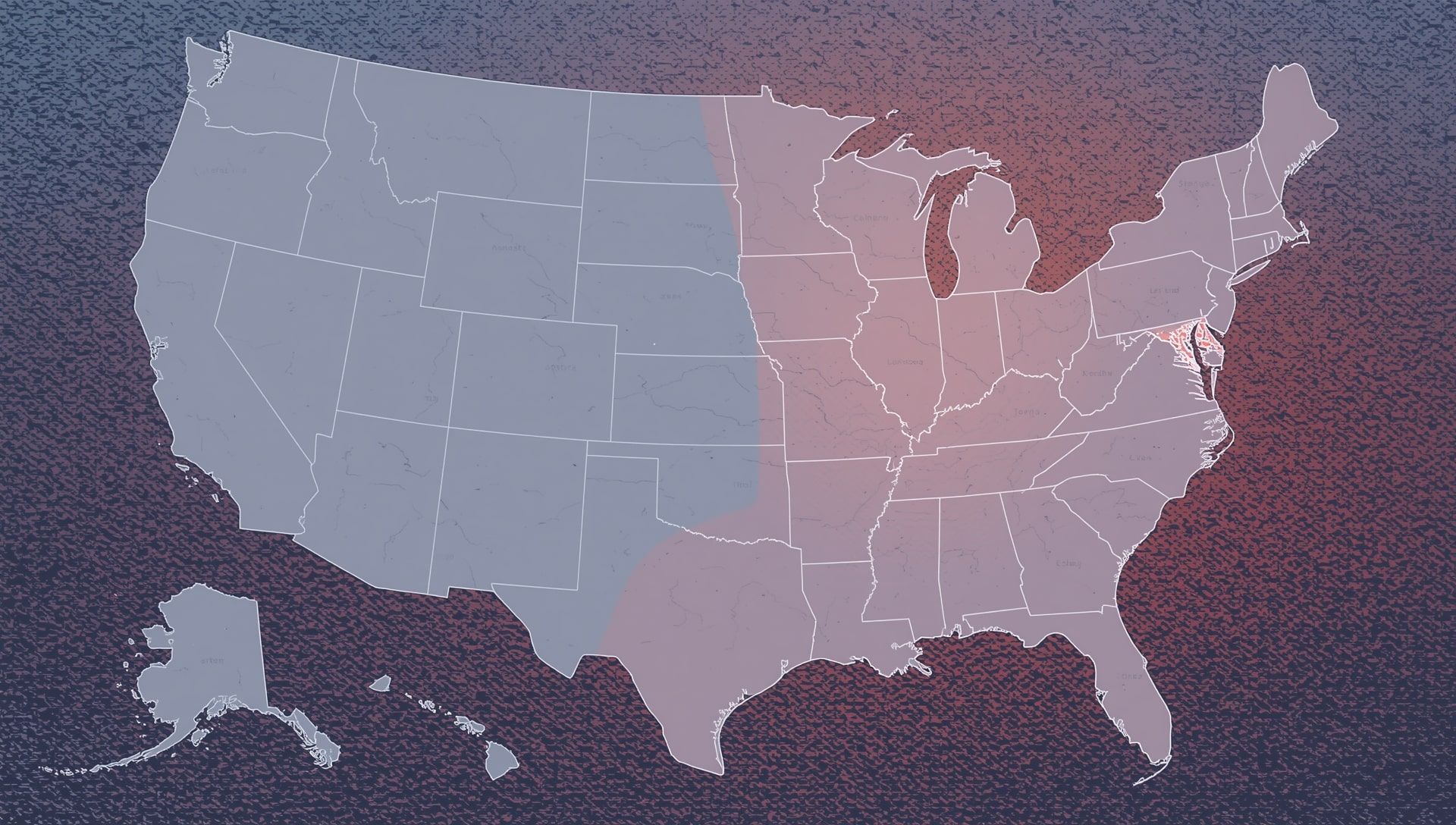

Public opinion has shifted dramatically in recent years. Many people now view DST as outdated, especially since its original energy rationale no longer applies. However, surveys often show a split between those who prefer lighter evenings (DST) and those who want to stay on natural Standard Time all year.

The debate is no longer just about energy, it is about health, convenience, and modern relevance. As more research shows the small or nonexistent energy gains, calls to abolish DST grow louder, echoing the permanent DST discussions in the U.S..

Looking Ahead

It is clear that DST no longer plays the energy-saving role it once did. While the concept worked in an age of limited technology and predictable routines, today’s energy patterns are shaped by factors far beyond daylight hours. The minimal gains observed in modern studies suggest that the time shift may be more symbolic than practical.

The future of DST will likely depend on whether governments prioritize stability, health, and efficiency over tradition. As climate policies evolve, many experts argue that focusing on renewable energy and smart grids would do more to conserve power than adjusting clocks twice a year.

Time for a New Kind of Efficiency

Daylight Saving Time may have once been a clever idea for its era, but its usefulness as an energy-saving measure has largely faded. The world’s energy systems have outgrown it. Rather than relying on time shifts to conserve power, societies are turning toward smarter, more sustainable solutions, just as explored in the purpose of DST and its modern reassessment.

In the end, the question is not whether DST saves energy, it is whether it still fits the world we live in. The answer, based on modern evidence, is increasingly clear: probably not.